On May 7th, the Society of Printers enjoyed its final meeting of the 2013/14 season. As secretary of the Society, I took on the unenumerated responsibility of supplying letterpress printed menus for each of the 8 dinner meetings, which occur on the first Wednesday of every month from October to May. It all makes for a gratifying pile, and as an avid collector of ephemera I am my own most reliable supplier.

But I only intended to print a menu for the October meeting, the occasion being the Charlie Rheault Lecture delivered by Simon Loxley, a British graphic designer, historian and author of Type: The Secret History of Letters and Printer's Devil: The Life and Work of Frederic Warde.

As the contact person for Simon's visit to Boston, I was determined to help show him a good time. This meant printing the invitation for his talk (with a huge assist from my friend Darrell Hyder at the Sun Hill Press) and a menu as a keepsake. For the invitation Darrell kindly allowed me the use of his Centaur and Arrighi types, and also access to his Heidelberg Windmill. But for the menu I had to use my own type, which immediately presented a problem: I didn't have very much of any one face. And very little at that of text faces below 18 point. I looked over my 3 cabinets rather doubtfully. A little 18-pt Bembo roman and 12-pt italic, and enough 14-pt italic in an old forme to set a single line; a case of 12- and 14-pt Romulus small caps; and 42-pt Augustea Inline for display. This situation was something of a burlesque of the usual inescapable battery of limitations faced by the hot-metal printer. But as a friend of mine likes to say, what cannot be helped must be endured. And I say, when you volunteer you can't complain.

I went with a tri-fold format to save some time, though the decision to use a second color pretty much nullified the savings. But Simon, and my SP colleagues, seemed to appreciate the gesture, and so all the anxiety of designing something classy with a handful of spare parts gave way to a feeling of accomplishment that sweetened an already memorable evening. I retired as the SP's menu printer on a high.

But the fact remained that I was desperately in need of type. As October progressed, the intervals between commissions allowed for more frequent visits to Sun Hill Press in North Brookfield. Darrell has an English Monotype Composition caster that has served him well over his 40-year career as, in me 'umble opinion, New England's finest country printer over that same span of time. Knowing that I had been trained to run a Monotype machine under John Kristensen at Firefly Press, Darrell kindly offered to let me cast usable quantities of type from his impressive collection of matrices whenever our schedules aligned.

Since I already had a case of 18-pt roman, the first typeface I chose to cast was Fournier, a charming, mellow and ornament-friendly 1924 revival of the 18th-century French original. Darrell had a 14-pt mold on the machine from his last job requiring composition, so I started there. It had been over a year since I had left Firefly, so my Monotype instincts were a little rusty. But after an hour or so of tinkering, the machine began producing beautiful shining rows of fresh type. Soon I had full fonts of roman, italic and small caps ready to lay into cases.

Fournier is a face I've admired from afar (mostly in Darrell's work), but had never used for any of my own projects, as it was one of the few historical revivals not in Firefly's awesome collection of book faces. Between business cards for a woodworker and a promotional piece for my shop, the type was in a comp stick just as quickly as it hit the case.

When the November SP meeting rolled around, Fournier Brain was at full froth. I came out of retirement to produce a menu that if nothing else would serve as another specimen of the type I could use to show prospective clients. The lima beans and red cabbage in the entree served as inspiration for ink colors.

Maybe I would have done it differently if I'd had a wider range of sizes, but even so this a much more organic design experience than the Frankenstein job turned in for October's meeting.

As December arrived I began thinking about a Christmas keepsake for family and friends. I had just acquired two small cases of type ornament and was eager to experiment. It occurred to me that the corner pieces of various separate but related designs might be persuaded to nest comfortably within a compound arrangement. The fact that I had only four sorts for each corner piece did not deter me from going forward. They were a bit worn, but as they were foundry-cast I knew they could handle a few more kiss impressions.

To the case of Fournier! Why not, as surely my last printed menu, do something a little nice for my fellow SP members for the holiday meeting? I went back to the tri-fold but with a twist, allowing for two panels each featuring a Christmas ornament with the initials of the Society and those of our host, the Club of Odd Volumes. Long after the meal has been digested, the design still satisfies.

It was becoming clear that I had committed myself to a printing program and that though I had no stated objectives to complete the set, once the Monday before the meeting rolled around I knew I would find myself with comp stick in hand trying to set a new speed record for design and production (the record is 5 hours. See: March). But let's at least give Fournier a break!

It happened that later in December I visited John Barrett's Letterpress Things, an awesome warehouse of salvaged printing equipment in Chicopee, Mass. He had recently bought the type holdings of Yale's Greer Allen, a connoisseur of stylish European foundry type. I was amazed to find that John had quite a bit of Weiss in various sizes still available for sale. I've had a borderline irrational love of Weiss for years, though I never seriously thought I would be able to obtain it, such is its rarity and the low voltage of my purchasing power. But the delivery of a few carving jobs allowed me to stand tall and take into the shop Allen's Weiss and, huzzah!, his 12- and 14-pt Romulus roman and italic to go with my case of small caps. I was pretty sure I knew what type I'd be using for January's menu. The prudent printer would have chosen either Weiss or Romulus. I chose both!

Perhaps not natural bedfellows, I grant. The two faces reflect much of the personalities of the designers, Weiss a full-blooded Teuton, Van Krimpen the dead-serious Dutchman. I'm still not quite sure I pulled this off, but it was fun while it lasted.

February saw Fournier's inevitable, triumphant return with a design that ratcheted up the complexity factor through too-clever-by-half ornamentation and a fussy fold. There was only one problem: thanks to a huge blizzard the SP meeting was canceled. Perhaps it's just as well that this menu saw only limited release amongst close friends and a few fellow printers. If you're going to swing for the fences, you better hit it out of the park. The fact that not everyone got the typographic joke could be taken as a sign that it was a ground-rule double at best. I'll give you a hint: the entree was salmon.

I thought it would be fun to make it look like the salmon was swimming upstream, achieved by careful placement of the lower ornaments so that they were half-revealed by the fold. The 12-pt Bell italic lowercase "p" gave the salmon just the right look of flinty determination, and the addition of the morticed ornament for a lower jaw was a touch of verisimilitude and the clue, I thought, that gave it away. Can't win 'em all, I s'pose.

Fortunately March brought better weather and an opportunity to practice some restraint. What better way to keep things simple than to allow yourself five hours to design, typeset and print the job. The speaker, Jesse Ragan, was giving a talk about his experience digitizing the experimental type designs of Rudolph Ruzicka. It seemed appropriate that the menu be set in his Fairfield with the accompanying ornaments, which meant a drive into Firefly the morning of the SP meeting for a rendezvous with the Linotype. This machine and I have always gotten along reasonably well. During my apprenticeship with John it was the first piece of typecasting equipment to which I was introduced, and though I had my fair share of molten lead eruptions and frustrating setbacks, I always had the sense that the machine really did want to work properly, really. But I was worried that I had been away from the literal hot seat for too long, that I'd run out of time before I even finished casting the type. Actually, it was just like riding an enormous dangerous bicycle without any wheels.The trickiest part was overcoming the false start with the ornamental design. Instead I inadvertently created an optical illusion, setting the rectangular ornaments in a pinwheel fashion that look as though they're about to spin away from each other. The cool baby blue was a nod to Ruzicka's springy pastelle palette.

By the end of March I had acquired various sizes of Perpetua, Joanna and the 48-pt Gill Floriate, and so the April menu practically set itself. As a lettercarver I think I'm required by law to love Eric Gill's lettering and type design, and I do, though my appreciation of the man is, ah, what's the word, complicated. He once said, "In inscription-carving, while we may remember Trajan lovingly in the museum, we must forget all about him in the workshop." I feel the same way about Gill. Modern biographies of the man have turned his admirers into apologists. But never mind. For the menu I decided to accentuate Joanna's lovely narrowness with a skinny format, and something suitably inscriptional on the cover.

I was delighted by how nicely the border played with the Floriate, which is so freakish that, true story, I once passed on a chance to acquire it from Stinehour Press during a type sale because it was too silly. I'm very glad the days of not-having-it are over. My eyesight is a little keener now.

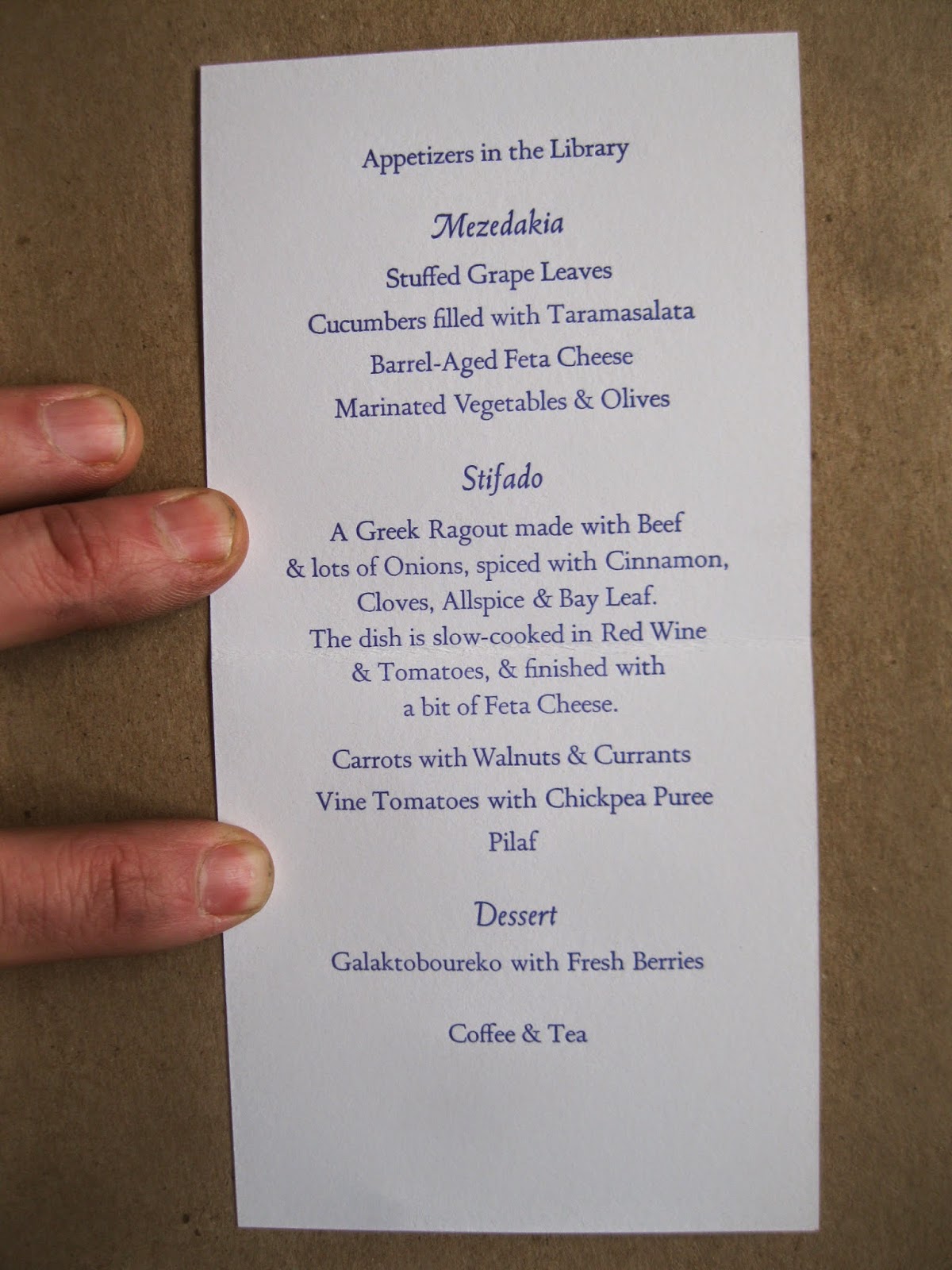

And then we came to May. The End. Well, almost. The story is the same but the type is . . . very different. Remember when I raved about Greer Allen's taste in type? Back in the 1960s he acquired four sizes of Rudolf Koch's Jessenschrift from the son of Joe Graves (Gravesend Press), a protege of Victor Hammer, who was himself a friend and protege of, wait for it, Rudolf Koch. I had seen the type at John Barrett's during three consecutive visits, increasingly amazed that no one had scooped it up. Though I didn't have any immediate need for it, there was a very great want and just enough room in the budget to take home this historic type, incidentally the only face that literally has my name on it. As is my established practice, as soon as I bring type into the shop I have to use it, if only to have a specimen handy. Enter: May's menu.

Embellished with an anonymous cut of rogues engaging in louche behavior, the last menu of the season also features, for the first time, something of a colophon, which was basically just an excuse to use the "Printed in USA" ornament. But it was also a personalized wink to the SP archives, which is now thickened somewhat by a year's worth of one printer's donated dinner ephemera. Now that the set is complete, I can officially definitely retire. Maybe.